What if a problem is NP-hard?

Why some problems resist quick solutions, and how we cope anyway?

The Pizza-Cutting Problem

Picture this: When there’s a game of cricket, 5 of us, in my hostel dorm, will decide to skip the food in the mess, and order a large pizza. Now comes the eternal problem, how do you cut it so that everyone is hapy? One person wants a larger slice, another wants a smaller one, and someone refuses onions altogether. And no matter what you do, somebody complains more than the commentator in the game.

It sounds funny, but this situation mirrors a whole family of problems in mathematics and computer science. Problems that feel simple on the surface but explode in complexity when you try to solve them perfectly. These are the problems we call NP-hard.

Sidebar 1: What is “P”?

P = Polynomial time.

A problem is in P if there’s an algorithm that solves it in time proportional to a polynomial in the input size nnn, e.g. O(n^2), O(n^3).

Polynomial growth is considered “efficient” compared to exponential growth like O(2^n), which becomes impossible even for modest n.

What does NP-hard actually mean?

In computational complexity, we classify problems according to how quickly they can be solved as they grow larger.

P — the class of problems solvable in polynomial time, i.e., problems for which we can find a solution in time bounded by some polynomial function of the input size n, such as O(n^2) or O(n^3).

NP — the class of problems where a proposed solution can be verified quickly (in polynomial time), even if we don’t know how to find it quickly.

Now, a problem is NP-hard if it is at least as hard as every problem in NP. Putting this in another way: if we had a fast algorithm for one NP-hard problem, then all problems in NP could be solved fast as well. Formally, we capture this with the idea of polynomial-time reductions:

Sidebar 2: What is a “reduction”?

A reduction is like translating one puzzle into another.

If you can turn problem A into problem B quickly, then solving B automatically solves A.

Example: “If I can solve your Sudoku puzzle, then I can solve your crossword too, because I’ve found a way to convert crosswords into Sudokus.”

Thus, to prove that a problem Q is NP-hard, we reduce a known NP-hard problem P to it in polynomial time. This is the mathematician’s way of saying:

solving Q efficiently would also solve P, and therefore every problem in NP.

An Example: Guarding the Town

Imagine organizing a neighborhood watch. The town has intersections (vertices) connected by streets (edges). Volunteers stand at intersections, and each volunteer “covers” all streets meeting at their intersection.

The question is simple: what’s the smallest number of volunteers needed to cover every street? This is the classic Vertex Cover problem.

It looks manageable, but finding the absolute minimum cover often requires checking an exponential number of possibilities. The difficulty isn’t just bad luck; it’s a structural property of the problem itself. By reduction from another known NP-hard problem (3-SAT), researchers show that Vertex Cover is also NP-hard. The essence of the proof is: if we could solve Vertex Cover quickly, then we could also solve logical puzzles like 3-SAT quickly, and thereby every other problem in NP.

Below is a sample construction of (x1 V x1 V x2)(!x1 V !x2 V !x2)(!x1 V x2 V x2) and it's cover in the constructed graph, which will yield values of x1=FALSE and x2=TRUE:

Does NP-hard mean hopeless?

Not at all. NP-hardness is not a death sentence; it’s more like a warning label. It tells us: “Don’t expect a universal fast algorithm unless you can also resolve the famous P=NP question.”

Sidebar 3: Why is P vs NP a million-dollar question?

The Clay Mathematics Institute has listed it as one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems.

If P = NP, then every problem for which solutions can be checked quickly can also be solved quickly.

That would upend computer science, cryptography, logistics, biology, you name it.

The prize? $1,000,000.

So far, no one knows the answer.

But in practice, we solve NP-hard problems all the time. How?

Approximation algorithms

They provide solutions that are guaranteed to be within some factor of the optimal. For Vertex Cover, for instance, there’s a simple 2-approximation: you may not get the fewest possible volunteers, but you’ll never use more that twice as many as necessary.

Sidebar 4: Approximation in action

Example: Vertex Cover.

Exact solution = NP-hard.

But there’s a simple approximation:

Repeatedly pick an uncovered edge.

Place volunteers at both endpoints.

This guarantees at most twice as many volunteers as the minimum needed.

In practice, that’s often more than enough.

Heuristics

They give “good enough” answers quickly, especially when there are no guarantees but practical performance matters (think airline scheduling or route optimization).

Special Cases

Some cases often admit efficient solutions. The Knapsack problem, for example, is NP-hard in general, but it can be solved in pseudo-polynomial time O(n^2 c_max), which is entirely feasible for many real applications.

Exact solvers

They use clever optimization, pruning, and modern hardware to crack surprisingly large problem instances, even though worst-case theory says it’s hard.

So NP-hardness doesn’t mean “throw in the towel.” It means “be smart about your approach.”

Small instance → solve exactly

Special case? → use a specialized algorithm

Need a perfect solution? → exact solver

Otherwise → approximation or heuristics

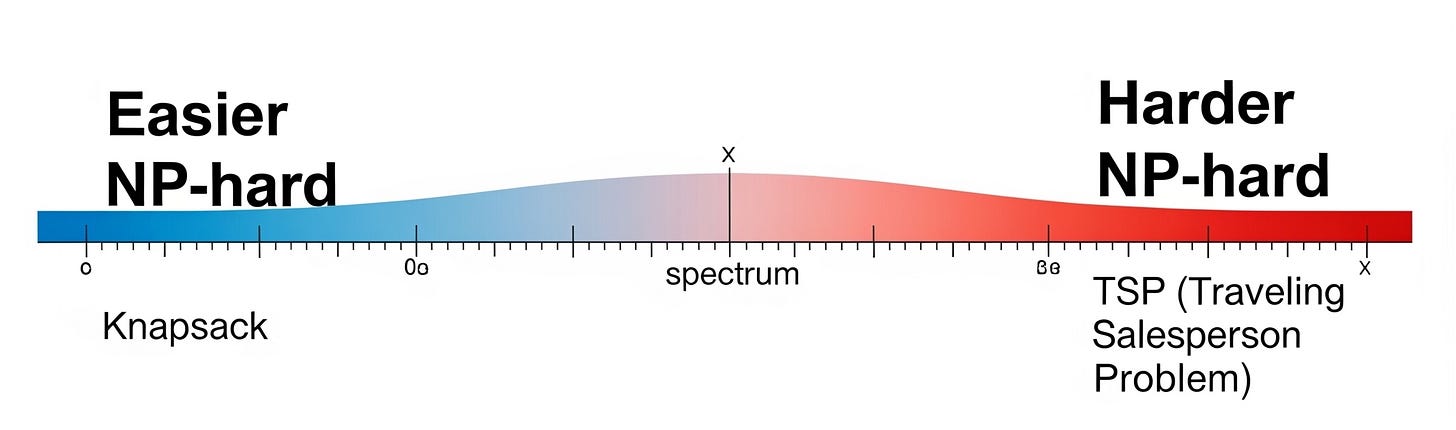

Not all NP-hard problems are created equal

It’s tempting to think that all NP-hard problems are equally intractable, but their difficulty varies greatly in practice.

The Knapsack problem often feels “easy enough,” because pseudo-polynomial algorithms can handle realistic input sizes.

The Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), by contrast, remains NP-hard even when all edge weights are just 1 or 2. Here the challenge isn’t large numbers, it’s the combinatorial explosion of possible routes.

This contrast shows that NP-hardness is a theoretical unifier, but practical behavior can differ enormously.

When we say a problem is NP-hard, we’re not saying it’s impossible. We’re saying it sits at the frontier of what we understand about efficient computation. For everyday practitioners, NP-hardness is not the end of the story but the beginning of strategy: should we approximate, restrict, optimize, or brute force?

So the next time your pizza party dissolves into debates about slice fairness, remember: you’re not just dealing with hungry friends, you’re brushing up against the same complexity barriers that computer scientists wrestle with. And the real question isn’t “Can this be solved fast?” but rather: “How do we outsmart intractability?”

~Ashutosh

Loved this ,specially the part "When we say a problem is NP-hard, we’re not saying it’s impossible. We’re saying it sits at the frontier of what we understand about efficient computation"

Exactly the major question is: "What should be the strategy to solve?"... Loved this :)